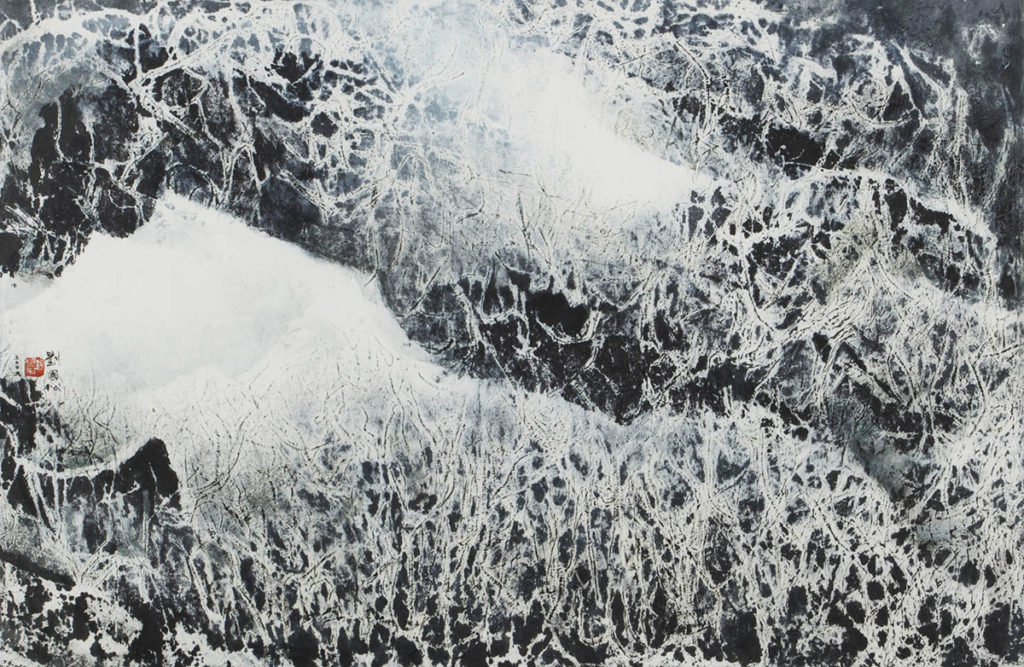

What Liu Kuo-sung’s Icy Tree with Silver Branches Conveys Is Perseverance

by Timothy Chang

Set against an icy outcrop, clusters of snow-clad branches dominate the painting. Despite the weight of winter snow, the branches remain upright and shoot toward the sky, patiently waiting for the arrival of spring. The metaphor of perseverance in winter scenes is a prevalent motif in the Classical tradition, dating back to the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127), when monumental landscapes emerged as a distinct genre. As the genre developed, physical attributes of nature became equated with character traits and ideals upheld by the literati class, as seen in Fan Kuan two monumental landscapes, Desolate Temple in Snowy Mountains in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and Snowy Scene of Wintry Trees in the Tianjin Museum. As for Liu Kuo-sung, perseverance was a trait upheld by the artist himself.

During Liu Kuo-sung’s time as an art student in the 1950s, the concept of Modern Art was rejected by elite ink painting circles of Taiwan, and traditionalists such as Pu Xinyu, and Huang Junbi dominated academia. Facing criticism from conservatives within the Department of Fine Arts at National Taiwan Normal University, upon graduation in 1956, Liu Kuo-sung founded an independent art movement called the Fifth Moon Group, dedicated to promoting Modern Art. The Group’s success brought international attention to Liu’s art, and in 1966 Liu received a prestigious grant from the John D. Rockefeller III foundation, which in turn led to the launch of a promising career in the US. Liu’s success abroad prompted a reevaluation of his art in Taiwan, and in 1968 he was awarded as one of Taiwan “Ten Outstanding Youths.”

Today, Liu Kuo-sung is of course widely recognized throughout the US, Europe, Taiwan and Mainland China as a distinguished artist and a pioneer of Modern Art in Taiwan, who played an indispensable role in the development of ink painting from its traditional roots to its contemporary form. However, often forgotten is the rejection and hardship Liu faced early in his career. Without perseverance and key breakthroughs, the direction of Liu’s art could have been drastically different. If he had conformed to the traditions of his time, like branches collapsing under the weight of heavy winter snow, Liu’s art would have never taken on the unique and Modern dimensions it is known for today.

Related Journals

Catalog Entry

The Scripture of a Missionary of Modern Ink Painting II

This painting reveals the influence of Taoism on Liu Kuo-sung’s art, particularly the philosophy that Yin and Yang is the source of all things. Yin and Yang are not to be understood as two opposing forces, but rather as two parts of the same whole, working in unison, creating all life in the universe.

Liu Kuo-sung, Light Snow, 1963 © The Liu Kuo-sung Archives

Catalog Entry

The Scripture of a Missionary of Modern Ink Painting II

Uncommon among Liu Kuo-sung’s oeuvre, the subject matter of this painting is exceptionally personal. Its inspiration comes from his wife Li Mo-hua’s eyebrows. Back when the couple first began dating, Liu was immediately drawn toward her eyebrows and the strong personality they conveyed.

Liu Kuo-sung, Pressing on the Brow, 1964 © The Liu Kuo-sung Archives

Catalog Entry

The Scripture of a Missionary of Modern Ink Painting II

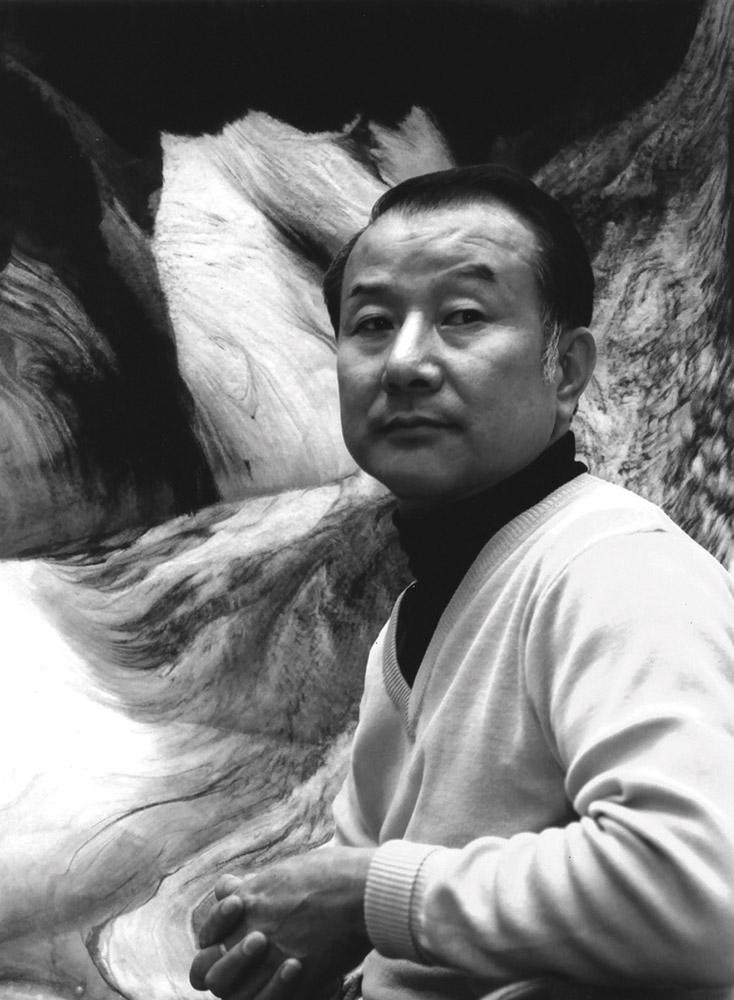

Starting in 1977, Liu Kuo-sung spent nearly a decade exploring and perfecting his technique of “Water-rubbing.” This dedication illustrates Liu’s “revolution against the brush,” and the notion that great painting can be created with or without the brush. Mountain Light blown into Wrinkles is a representative work from this inspiring period of experimentation and creativity.

Liu Kuo-sung with Mountain Light Blown into Wrinkles. Photo: Courtesy of Liu Kuo-sung © The Liu Kuo-sung Archives