Conscious Landscape – Guo Kai Solo Exhibition Catalog, Lofty Culture & Art, 2014.

by Elaine Suyu Liu (Translation by Timothy Chang)

The famous American essayist Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862) once wrote:

Men say they know many things;

But lo! They have taken wings — The arts and sciences

And a thousand appliances;

The wind that blows

Is all that anybody knows

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, or Life in the Woods is recognized as his greatest literary classic on natural living. With his use of simple and eloquent language, Thoreau advocates a spiritual return to the basics, which strikes at the very heart of the materialistic nature of modern society. Centuries later, the Walden is still celebrated by those wishing to escape the mundane matters of daily life, and to once again return to nature’s fond embrace, as a hermit or philosopher.

In my opinion, Guo Kai’s paintings, in of both spirit and form, are very similar to the thought of Henry David Thoreau. They both advocate the escape from urban living, and the return to a natural environment. In terms of their highest ideal of living, it is to be one with nature. For Guo and Thoreau, they change with the seasons and go where the river takes them, where every landscape is an inspiration for either an essay or a painting.

However, Guo Kao’s artworks also carry a sense of Eastern philosophy, much like a traditional Chinese landscape painting. Of course, Guo’s art is best represented by his iconic landscapes of Southern Anhui. Born and raised in the basin between Yangtze and Huai rivers, Guo is comfortable and content in his native land, where the luscious and tranquil atmosphere of the Southern Anhui countryside is brilliantly captured by his art. Guo’s quiet and serene landscapes genuinely invite the viewer into his seemingly distant dream world. As the ancient Chinese believe; to wander quietly afar is to have wisdom.

Unlike most contemporary Chinese artists, Guo Kai never followed the trend of migrating to major cities or painting in a popular art village. Moreover, unlike those who live and work in the studio, Guo enjoys painting from life outdoors. He leaves behind the hubbub of the city, and places himself in a sparsely populated landscape, into the serene nature of the Southern Anhui that he loves. Alone with nature, Guo is free from the influences and social pressures of artists from art villages. His sole artistic inspiration comes from the land itself; the mountains, the rivers, and the life it creates. And from the land, there on the spot, he simply sketches and paints what his eyes see, without cameras, projectors, or computer graphics, that is without any external assistance from technology. In this way, the composition on the canvas, is a direct representation of his artful observation of the world – seen through his eyes, composed by his mind, and carried out by his hands – without any unnatural angles or distortions by camera lenses. Through this interactive process, he not only develops a high familiarity, but also an emotional bold with the landscape, something a painter behind closed doors can never fully understand.

The land of Anhui is famous throughout China, known for its abundance of culture since dynastic times; the definitive, of course, is the traditional architecture of Huizhou, or modern-day Huangshan City. The so-called Hui style of architecture is an embodiment of the customs and beliefs of the people of Southern Anhui. It is unique in style, sophisticated in form, and an architectural achievement of harmony between man and building. Much like the Chinese proverb “a land supports a people,” born and raised in Southern Anhui, Guo Kai is a Southern Anhui person. Brought up among the mountains and streams, Guo has not only develop a delightful temperament toward nature, but also with his elegant intelligence and understanding of the land, he can fully appreciate the artistic and poetic qualities of the Southern Anhui landscape, where anything can be art, and anything can be poetry; often intertwined upon the composition of his canvas.

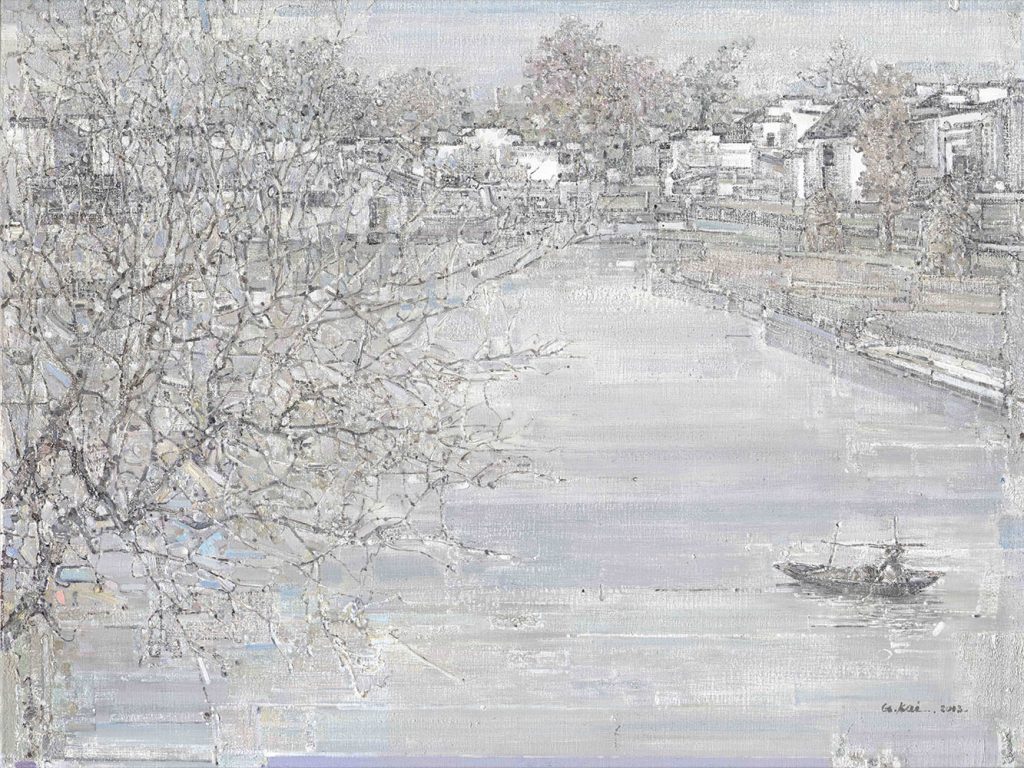

White-washed walls, black roof tiles, and horse-head walls are the iconic architectural features of the Southern Anhui style. Naturally they serve as scenic images for painters and photographers alike. Although Guo Kai is not the first in depicting this time-honored landscape, he skillfully avoids making cliches through his conscious attitude in facing the subject matter. By studying each detail of the Hui architecture, as well as the governing philosophy behind the structure, Guo develops an unique understanding of the patterns and rhythms formed by the walls and roofs, and ultimately how they interact with the surrounding landscape. In representing the this natural rhythm, Guo’s composition is created by small patches of light shades and colors, which interact with one and another, creating a rich and harmonious atmosphere, like pieces on a puzzle. In this way, Guo not only expresses the sense of life drawing from nature, but also creates an unique and distinctive style for himself as an artist.

In Guo Kai’s paintings, the intrigued viewer often finds tiny dots of black, white and pink, scattered across the composition. These dots are intentionally planted by Guo as focal points; a visual device to attract the attention of the viewer, and to guide his or her eyes from one area of the canvas to next. Thus the viewer not only carefully examines every detail of the composition, such as the pressure of the brushstrokes and texture of the paint, but also further experiences the playful interaction between the tiny dots and larger patches of color. And from the buildup of shapes and colors, the viewer’s gaze is brought back to the overall composition. Therefore, while landscape paintings are generally viewed as a whole, in terms of the larger atmosphere, Guo’s visual devices and keen attention to detail invite the viewer for a more intimate and exciting look into his artwork, which ultimately enhances the visual experience.

Those who know Guo Kai personally, all know he as a very clean and tidy person, in both appearance and persona. This attitude is translated into his life and art, starting from a tidy home and an organized studio. In his paintings, from the overall composition to the slightest line or finishing dot, each and every detail on the canvas is deliberately and carefully orchestrated. The same precision can be said about Guo’s use of color. While his images often appear monochromatic at first glance, they are in fact composed of a main color supplemented by many colors in correlation with it. By selecting contrasting supplementary colors, such as light green or pink hues juxtaposed with simple shades of bluish grey, the different patches of color interact with one and another, creating a moving dynamic effect. However, as the different shades and colors are all derived from one main color, the overall composition appears unified and peaceful.

The beauty of Southern Anhui’s architecture is how the whited-washed walls and black rooftops stand in unison with the surrounding landscape. Spread harmoniously across the horizon, with mountains serving as a backdrop, the curvy lines of the horse-head walls are like brushstrokes on a painting. Guo Kai captures this essence brilliantly by representing the patterns and rhythms formed by the architecture and landscape. Through repetition, he emphasizes the horizontal lines of the image, and thus creates a calming sense of rhythm. Also, his compositions are deliberately leveled and stretched by forgoing the use single-point perspective, which tricks the eyes, and further enhances the dreamlike atmosphere.

Traditional Chinese ink painting techniques of preserving negative space (liubai) and flying-white brushwork (feibai) are remarkable features of Guo Kai’s artwork. Whereas Western oil painting is generally created by accumulating and mixing multiple layers of paint, brushstrokes of traditional Chinese ink painting cannot be layered or altered. Moreover, ink painting cannot produce the color white with brushstrokes, and must instead preserve the original color of the paper or silk as white. Although Guo Kai’s medium of painting is oil paint, he nonetheless chooses to adhere to this tradition, by leaving fragments of the primed canvas visible and unadorned with paint. Moreover, Guo often paints with a dry brush, thereby leaving dry spots in the wake of the brushstroke, essentially in the same manner as the flying-white brushwork of Chinese calligraphy. Through the employment of these traditional techniques, Guo Kai has transferred the transcendental atmosphere of traditional Chinese landscape painting into the Western medium of oil painting, has ultimately demonstrated the rational deliberations behind his creative process.

From the subject matter of Guo Kai’s paintings, that is the life drawings of the Southern Anhui landscape, is an abundant sense of vitality from both nature and civilization. Mountains are depicted like standing monuments, while rivers are forged with the power of sustaining life. Trees and branches are painted as thriving and blooming. Even in winter scenes where the leaves have fallen and branches are bare, the trunks of the trees still remain tall and strong. Stone bridges and their reflections in the water are not only visually beautiful, but also inviting to the viewer, as it is easy to picture oneself walking across them. Ancient pagodas tower over the landscape, evoking glories of the past, while distant villages and rice paddies are present testaments to the continuity of traditional country life, of which Guo Kai quietly yearns for.

In Guo Kai’s landscapes, human figures are rarely shown. In this exhibition, only Sailing on a Secluded Lake of 2013 is painted with a clear human subject; a lone fisherman. In traditional Chinese painting, the motif of the fisherman symbolizes an escape and refuge from society and the pursuit of life as a hermit. Although I do not know for certain whether or not Guo Kai has this type of mentality, I can surely imagine most Chinese people relishing over this ideal. It is often said that China’s most beautiful scenery is landscape, while Taiwan’s most beautiful scenery is people, which is amusing and rather truthful. Henry David Thoreau once said “you must not blame me if I do talk to the clouds.” Guo Kai’s paintings are like Thoreau’s essays, they are both a heartfelt dialogues with nature. And as poet Tao Yuanming (365 – 427) would say, “there is already truth within, I need not argue more.”

Relatred Journals

Distant Sounds in Autumn Woods

Catalog Entry

Guo Kai’s oil on canvas work Distant Sounds in Autumn Woods illustrates a historic cultural region known as Huizhou, situated in what is now China’s southern Anhui province and northern Jiangxi province. In late imperial times, the region produced generations of merchants who conducted trade nationwide, but spent their wealth building their native community. The large estates and ancestral halls the merchants built were installed with their values of diligence, frugality, and education.

Guo Kai, Distant Sounds in Autumn Woods (detail), 2013 © Guo Kai

Attachment · Whispers 3

Catalog Entry

Bright blooming flowers cover the foreground of Attachment · Whispers 3. Two young women in plain white clothing stand behind the flowers, holding hands in a close embrace. In examining the relation between the foreground flowers and the sitters, the picture plane appears skewed. The flowers seem superimposed onto the composition, creating a sense of ambiguity that also relate to the nature and relationship of the two young women.

Guo Kai, Attachment · Whispers 3 (detail), 2022 © Guo Kai

Faraway Breeze

Essay

“I believe a painting should be like a poem, a song, or a beautiful prose. That is why painting a painting should be like writing a poem, singing a song, or writing a piece of prose.” – Fu Baoshi.

The first impression given by Guo Kai’s paintings is like that of a poem, a song, or a beautiful piece of prose. Poetry in painting has always been an integral part of classical Chinese painting, and Guo Kai’s paintings are particularly poetic. Plain and unadorned titles, such as Spring Stream, Winter Water, Reflection of the Bridge, or Quiet Pavilion, paired with his paintings become pieces of silent poetry.

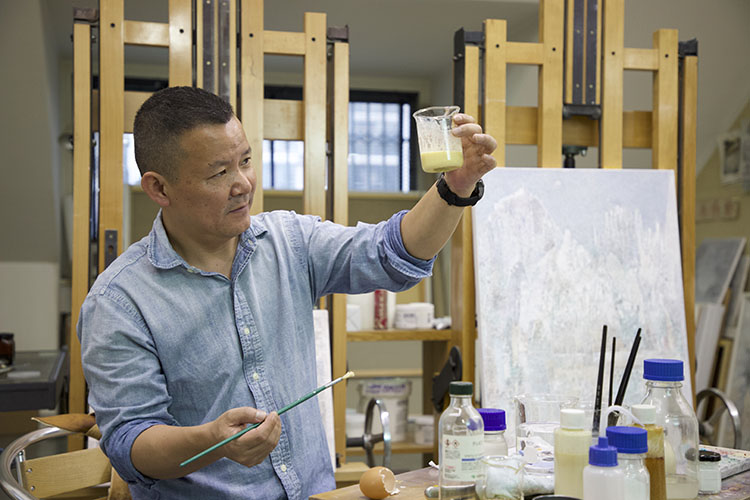

Guo Kai examines tempera paint, Hefei, Anhui, 2018. Photo: T. Chang