Faraway Breeze – Guo Kai Solo Exhibition Catalog, Lofty Culture & Art, 2018.

by Elaine Suyu Liu (Translation by Timothy Chang)

“I believe a painting should be like a poem, a song, or a beautiful prose. That is why painting a painting should be like writing a poem, singing a song, or writing a piece of prose.” – Fu Baoshi (1904 – 1965).

The first impression given by Guo Kai’s paintings is like that of a poem, a song, or a beautiful piece of prose. Poetry in painting has always been an integral part of classical Chinese painting, and Guo Kai’s paintings are particularly poetic. Plain and unadorned titles, such as Spring Stream, Winter Water, Reflection of the Bridge, or Quiet Pavilion, paired with his paintings become pieces of silent poetry. Not to mention the more classical titles, such as Early Spring Rain, Autumn Mountain Peak, Snowfall in Secluded Valley, or Empty Mountain Spring, which resonate strongly with the poetry of the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (1127 – 1279) Dynasties.

Landscape painting in the Western tradition was not embedded with strong poetic and personal emotion until the Seventeenth Century, with artists Claude Lorrain (1600 – 1682) and Jacob van Ruisdael (1628 – 1682). The art historian E. H. Gombrich said, “…it was [Jacob van Ruisdael] who discovered the poetry of northern landscape as much as Claude discovered the poetry of Italian scenery. Perhaps no artist before him had contrived to express so much of his own feelings and moods through their reflection in nature.”1

Jacob van Ruisdael was praised by the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 -1832) as a poet among painters. The subject matter of van Ruisdael’s paintings was almost exclusively landscapes, ranging from pastoral to marine. Unlike other Dutch painters of the period, van Ruisdael did not depict the scenery realistically as it appeared, but instead rearranged the compositional structures such as trees, clouds, and natural light as he saw fit, especially in his depictions of the sky.

Guo Kai, whose subject matter is also landscape, also draws upon personal emotion and intuition for his poetic images. Guo aims to maintain a “conscious landscape,” which he describes as “conscious and thus introspective, introspective and fanatic perceptions nourish the mind’s landscape.”2 He repeatedly reflects on a quote by the contemporary photographer Robert Frank (b. 1924): “I am always on the outside, trying to look inside, trying to say something that is true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there. And what’s out there is constantly changing.” An artwork is a projection of the artist’s inner world, and this coincides with Guo Kai’s artist statement: “what is important is not the landscape, but the image in one’s mind.”

Like for Jacob van Ruisdael, the sky and clouds also play important roles in Guo Kai’s compositions, often to the point of dominating over half of the image. In Snow & Mist, Purple Cloud, and Autumn Mist, the sky’s large ratio over the land creates a distant field of vision, poetically rendering the scenery grand and vast. Han Zhou (c. 1094 – ?) of the Song Dynasty wrote in his treatise on landscape painting: “the essence of mountains and rivers [i.e. the landscape] lies in the clouds.” The role of clouds in Chinese landscape paintings is not only a pictorial device for negative space, but also for the sense of movement. In comparison to stationary elements such as rocks and trees, clouds are uniquely dynamic and constantly changing, and with correct use bring the painting to life.

In contrast with the physical elements within a landscape, other elements that share the same semi-physical qualities as sky and clouds are mist and rain, which play important roles in Guo Kai’s paintings. Mist and rain gives Guo’s images an atmospheric sense of vastness and obscurity, which is reminiscent of the Taoist (Daoist) concept of Yin and Yang, and the balance between the physical with the non-physical. In order to represent the non-physical, Guo Kai developed an unique set of painting techniques specifically designed for this aesthetic, such as light muted colors, controlled and highly-articulated brushwork, the use of a very dry brush, wiping excess paint off the canvas, or allowing the paint to run freely down the canvas. From this idiosyncratic oeuvre of personal techniques, Guo Kai transmits the essence of traditional Chinese landscape painting in an aesthetic that is poetic and distinctly his own.

“The place of a life time, the dream of Huizhou.” Southern Anhui province, known in the past as the ancient state of Huizhou, is rich in historic buildings from the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1644 – 1911) Dynasties, as well as beautiful natural scenery, from which Guo Kai draws inexhaustible inspiration. Guo often travels to the countryside of southern Anhui to sketch from life, either with students or by himself. Going for weeks at a time, he has maintained this practice for over twenty years, and has set foot in every corner of the countryside, in every season, through rain and snow. In addition to sketching, he also takes photographs to capture the moment for further inspiration back in his studio.

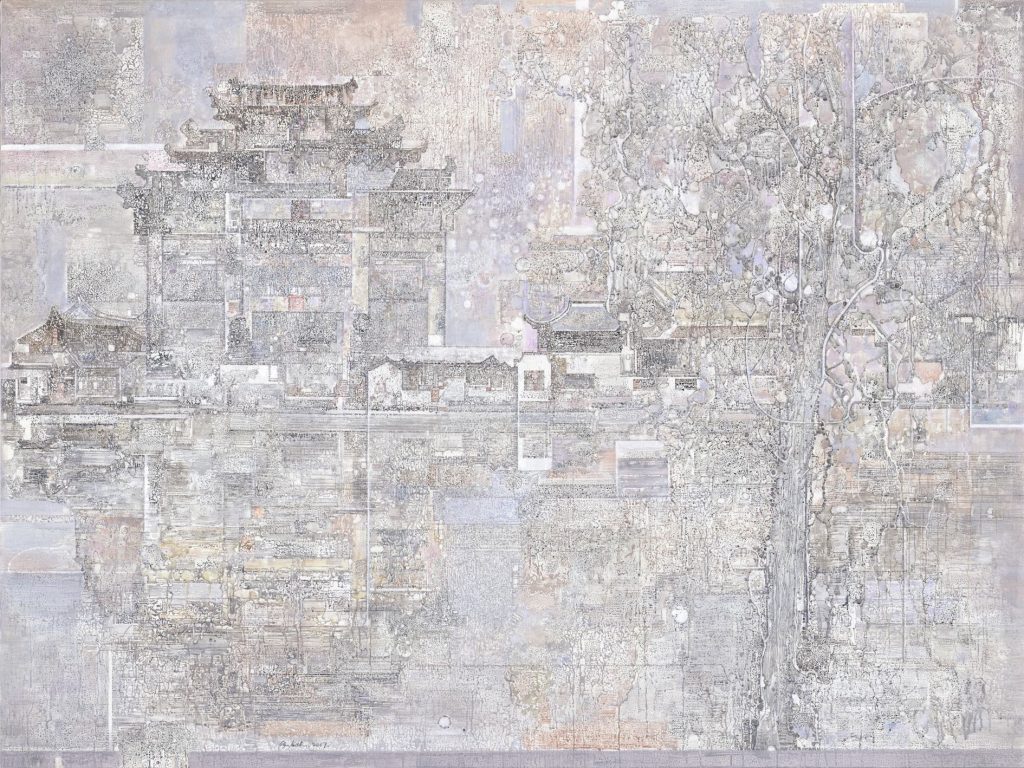

However, Guo Kai’s paintings are not realistic representations of the scenery, as he is far more interested in representing the conception of the scenery and what it conveys. In his works, the classic features of Huizhou, dark ceramic tiles and whitewashed walls, ancient temples and pagodas, or bridges and canals, are faithfully captured but deliberately reconstructed. Some compositions are simply the artist’s own imagination. Take for example, the village in the recent Misty Remote Village; the line of houses is a reconstruction of several structures from different photographs. Guo Kai values “intuition, such that intuition activates an authentic understanding and self.” He believes, “only through self-understanding can truth be expressed in painting.” This notion coincides with the ancient Chinese belief of painting from the heart, rather than the eye. However, Guo Kai does not abandon painting what he sees, and therefore his works appear seemingly realistic and yet surreal at the same time. In fact, the appeal of Guo’s works, besides to his heightened sense of aesthetics, is his unity of emotion and scenery, which in turn is a revelation of his outlook on life, in terms of nature, human life, and philosophy.

The use of high perspective overlooking a distance in certain works is a projection of Guo Kai’s grand outlook on nature and life. In works such as Pale Shadows of Floating Clouds I, Pale Shadows of Floating Clouds II, and First Snow Over the Ridge, the foreground and mid-ground is placed uniquely low, thereby raising the vantage point. The natural landscape and historic architecture is blended together in the distance, where black ceramic tiles and whitewalls walls are nestled between stretches of green fields and a backdrop of a rising mountains. By placing the viewer on a high vantage point overlooking the landscape from afar, Guo creates a vision of a distant utopia, seemingly accessible to the viewer.

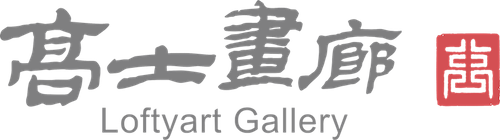

Guo Kai also makes use of long horizontal compositions. By structuring the composition on an expanded horizon, a panoramic sense of openness is created. Buildings of various heights are lined on the horizontal axis and set in front of densely packed trees, bobbing up on down across the axis. The undulating lines of buildings and trees are in turned echoed by the mountain ranges in the background, forming a visual rhythmic pattern in which every element is in perfect harmony. In order to further illustrate the sense of expansiveness, he often splits the composition onto two canvases. The visual advantage of a diptych is the sense of expansion created by the composition’s continuation from one canvas to another, as seen in Autumn Mist and Autumn Estate, in which the field of vision covering buildings and fields seem unbound and endless.

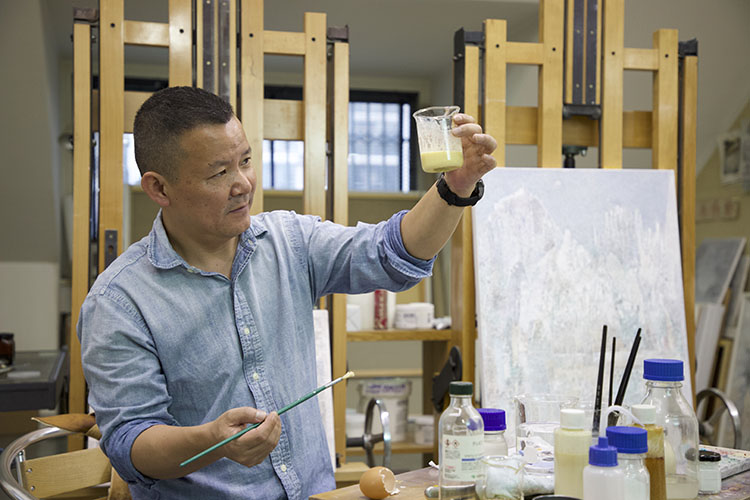

Where the Yangtze River cuts across southern Anhui, the land is ridden with rivers, waterways, and bridges. Traditional houses are often built right on the edge of the river, in a picturesque fashion. Guo Kai is particularly interested in the reflections in the water. In long horizontal compositions, he often reserves half of the image for the water’s reflection alone. In Autumn Reflection, Tranquil Landscape No. 2, Colors in Shadows, and Dream of Huizhou, more emphasis is placed on the water’s reflection than the scenery above, demonstrating Guo Kai’s interest in the water’s wavy and dreamy projection of the world, rather than the actual world itself.

Although Guo Kai’s field of study has always been Western painting, for which he went to Paris to perfect, his roots lie deep in the land of Huizhou, where the history and culture stretches back thousands of years. His identification with his homeland, his love for the native flowers and trees, his knowledge of the historical architecture are all recorded by his brush and canvas. Local icons such as monumental gateways or grand ancestral halls are repeatedly portrayed in his paintings. In Impression of Huizhou No. 1 and Ancient Square, the subject is represented from a distance, in which the monumental gateway stands out and dominates the composition, thereby symbolizing its social role in the village. On the other hand, in Huizhou No. 2 and Ancestral Temple in Spring, the building’s facades are directly presented in two-dimension. However, Guo Kai infuses the seemingly simple image with other painterly elements. In Huizhou No. 2, the composition is a complex deconstruction and reconstruction of various architectural details, symbolizing the building’s growth and decay over hundreds of years. Ancestral Temple in Spring demonstrates several of Guo Kai’s painting techniques, especially the technique of wiping paint off the surface of the canvas, while allowing a remainder of paint in the fine creases of the canvas. This creates a weathered look, which perfectly resembles the patina on an antique wall. In contrast with the aged building, bright colors and flowing lines of flowers and vines are added to the facade, thereby livening the composition.

Elegant colors are major features in the art of Guo Kai, in which the neutral color gray is a prominent theme. However, in the past three years, his overall gray-toned images are starting to show hints of bright colors, such as Colors in Shadows, White Bridge No. 2, and Autumn Estate. Despite the brighter palette, the painted image remains soft and elegant, due to his restraint in the use and placement of these colors, never in large clumps, and always neutralized by softer tones. More importantly, Guo Kai is particular in mixing the perfect tone before applying it to the canvas, and never allows paint to mix while on the canvas. Despite the use of thin paint, Guo’s paintings are far from being without surface texture. His textures are usually created by altering the paint after it has been applied, with different utensils, including a painting knife or paper towels. By removing paint rather than adding it on, the texture of his paintings recalls his restraint and control with color, as well as his general less-is-more approach and philosophy to painting.

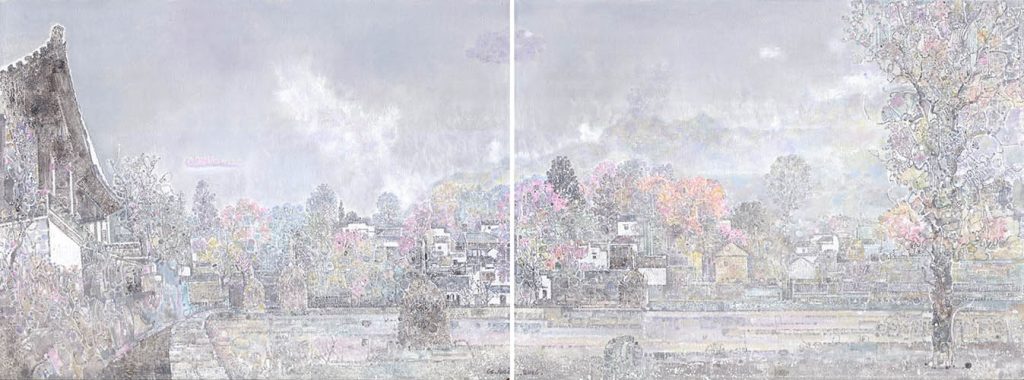

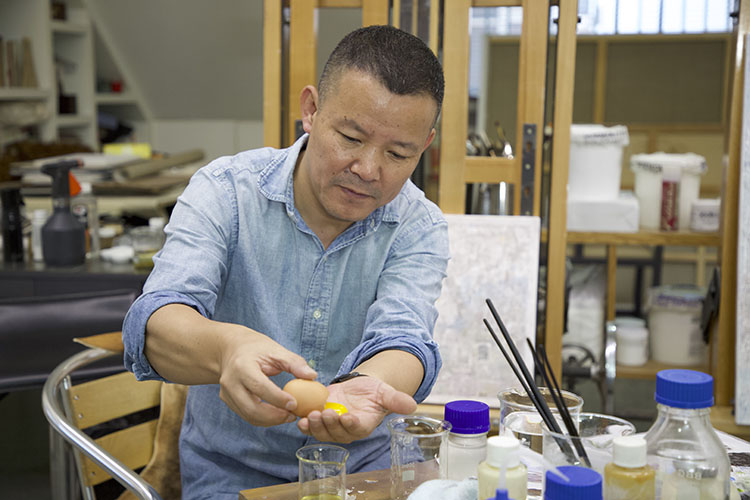

Also in recent years, Guo Kai has devoted himself in studying the medium of tempera, which requires mixing powdered color pigments into egg yolk, the binding agent for the pigments. Tempera allows the image to become more transparent and smooth, as paint itself is more translucent compared to oil paint, and therefore reflects light in a soft and silky manner. Guo Kai’s extensive study of the medium has allowed him mastery over the technique, as well as innovations in his art. He believes painting technique itself can become a subject matter, and the advancement in technique elevates the subject. Ultimately, his art speaks for itself, and always captures the viewer’s attention in wondering how it was painted, which has always been a personal goal of his.

Guo Kai often finds himself lingering in historic buildings and ancestral halls. He feels that the former inhabitants of the buildings are not distant from him, and can imagine the tales of the great families or the precepts of the ancestors being handed down to him. Although most of the historic buildings of Huizhou have stood there for three to five hundred years, compared to the long length of Chinese history, which traces back over four thousand years, the buildings are relatively recent and close to our times. This understanding of time is alarmingly close to mysticism, but Guo Kai does not delve into it. In any case, the ancient and bygone have always attracted him, and his photograph studies of patina on the antique walls number to the hundreds. In the past two years, his journey through ancient China has taken him pass the Ming and Qing dynasties, into the golden age of Chinese painting during the Song and Yuan (1271 – 1368), and the spirit of past masters are born again in his recent works. In Mist & Pine, Snow Over Autumn Peak, Blue Mountain, and Empty Mountain Spring, one can sense elegant and enigmatic nature of ancient paintings reemerging on Guo Kai’s canvases and brought back to life by the touch of his brush, like a faraway breeze gently carrying the spirit of the Song and Yuan dynasties.

Relatred Journals

Catalog Entry

Guo Kai’s oil on canvas work Distant Sounds in Autumn Woods illustrates a historic cultural region known as Huizhou, situated in what is now China’s southern Anhui province and northern Jiangxi province. In late imperial times, the region produced generations of merchants who conducted trade nationwide, but spent their wealth building their native community. The large estates and ancestral halls the merchants built were installed with their values of diligence, frugality, and education.

Guo Kai, Distant Sounds in Autumn Woods (detail), 2013 © Guo Kai

Catalog Entry

Bright blooming flowers cover the foreground of Attachment · Whispers 3. Two young women in plain white clothing stand behind the flowers, holding hands in a close embrace. In examining the relation between the foreground flowers and the sitters, the picture plane appears skewed. The flowers seem superimposed onto the composition, creating a sense of ambiguity that also relate to the nature and relationship of the two young women.

Guo Kai, Attachment · Whispers 3 (detail), 2022 © Guo Kai

Essay

Conscious Landscape

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, or Life in the Woods is recognized as his greatest literary classic on natural living. With his use of simple and eloquent language, Thoreau advocates a spiritual return to the basics, which strikes at the very heart of the materialistic nature of modern society. Centuries later, Walden is still celebrated by those wishing to escape the mundane matters of daily life, and to once again return to nature’s fond embrace, as a hermit or philosopher.

Guo Kai, Paris, France, 2009. Photo: Courtesy of Guo Kai