Xue Song’s Role as an Artist in Contemporary Culture

by Timothy Chang

Fire and Water – The Art of Xue Song, Lofty Culture & Art, 2022

Xue Song is an artist who is conscious of his craft. As a professional, he maintains a routined schedule. His trademark technique of fiery collage has been perfected into a science. From the initial compositional outline, to the selection, branding, and pasting of collage scraps, to the final applications of acrylic paint and protective varnish, each stage is completed in a designated station in his Shanghai studio. On an existential level, Xue Song acknowledges the time and place of his role as an artist. As a Chinese Contemporary artist, the challenge of Western art has undeniably shaped his practice. Consciously working within this premise, he addresses his own identity and confronts the complex history that has shaped him and the fast-changing society in which he is a part of. In this way, Xue Song’s evaluation of himself as an artist ultimately corresponds to the value of his art.

The distinction between artist and craftsmen lies in individuality. This is a quality that the latter lacks, while the former has strived in creative ways to leave their mark, and in doing so establish and at times re-invent their roles as artists. The earliest instances of artists leaving their signatures are found in the early Renaissance, when the role of co-operative guilds diminished in favor of individual artists. During the same period, artists began inserting portraits of themselves, often onto secondary figures in historical or religious scenes, in what became known as inserted self-portraits. In Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens of 1509 to 1511, the artist portrays himself as one of the philosophers among Plato and Aristotle, thereby presenting himself not as a mere painter, but as a thinker. As the distinction of artist and craftsmen further progressed in the Baroque period, artists began actively acknowledging and identifying themselves as artists. In Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting of 1666 to 1668, the subject of the painting is painting itself. The artist depicts himself in the act of his craft, reenforced with tools of his trade as well as symbols to suggest his extensive learning and culture. In wake of the Realist movement, when scenes of ordinary life gained triumph over historical or religious ones, Gustave Courbet celebrated his role as an artist in The Painter’s Studio of 1855. On a monumental canvas spanning over five meters in length, Courbet meticulously listed allegorical representations of various influences on his career, and thus commemorates himself as an artist.

By the Modern era, artists’ visual commentary on art dove even deeper, from the practice itself to art historical and theoretical roots. From 1954 to 1955, Pablo Picasso created a series of fifteen paintings titled Women of Algiers, which were inspired by Eugène Delacroix’s 1834 painting The Women of Algiers in their Apartment. While the tradition of modeling paintings after past masters was common, notably in the genre of nudes, Picasso’s approach was drastically different, as his abstract rendition bared little resemblance to the source material. Rather than an homage that pays tribute to the past in a linear fashion, the manner and sheer confidence of Picasso’s approach demonstrated a drastic change in the course of art history. As much of this change may be attributed to the artist himself, Picasso was keen to commemorate it and thereby secure his place in history. This notion of making history by challenging history is exemplified by Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. of 1919. Regarded as one of his readymades, where an ordinary object is elevated to the status of art, the work is a cheap postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s early 16th-Century painting Mona Lisa, on which Duchamp drew a mustache and beard. Duchamp’s satire and apparent disregard for arguably the most iconic and revered masterpiece of Western art, demonstrates his challenge to tradition and high institution. Identifying as an outsider, Duchamp saw his calling as one to reject the conventions of the art world, going as far as attempting to quit art altogether later in his career. In the post-war period, Andy Warhol on the other hand, took a completely opposite approach. Due to his early career in advertisement and illustration, Warhol was initially treated also as an outsider; however, rather than directly reject conventions, he cleverly changed the art world from within.

Upon the debut of Andy Warhol’s thirty-two screen prints Campbell’s Soup Cans in 1962, critics slammed the work; not only was the subject matter perceived as mundane, they also argued that the mass-production method of screen printing deprecated its value. Regardless of the several anecdotal stories on the choice of the soup cans, the choice nevertheless reflects a reaction to the movement Abstract Expressionism, which Warhol felt alienated by due to its highly intellectual nature. The choice also reflects a positive commentary on Modern life, which the artist embraced, especially in this instance, Modern technology and the means of mass-production it allowed. Warhol’s interest in popular culture coincided with the rise of the middle-class in post-war United States, where consumer items became readily available to nearly all members of society. One such item was celebrated in his series of Coca-Cola Bottles starting in the 1960s. Warhol relished the fact that anyone from the political elite, to Hollywood celebrities, to himself as an individual had access to and often drank the popular soft drink.1 While Warhol’s unapologetic embrace of popular culture, most notably consumer culture, proved controversial, it nevertheless resonated strongly with patrons. His New York studio, called The Factory, quickly became a renowned gathering place for bohemian intellectuals, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy patrons alike, many of whom Warhol courted for portrait commissions. By pairing portraits of celebrities like Marylin Monroe alongside his own self-portraits, in the same way Renaissance artists’ inserted their self-portraits among historical or religious figures, the artist elevated his persona to that of his sitter, and thereby enjoyed the fame and success it entailed.

Upon wide-spread commercial success in the 1980s, Andy Warhol sought to express his view of art as a commodity in explicit terms. Revisiting a motif he conceived in 1961, Warhol began an extensive series of drawing, paintings, and prints of the Dollar Sign in 1981. Like the Hollywood celebrities that he frequently associated himself with, Warhol knew that as an artist, he was part of a highly lucrative industry, and at this point in his career he had created substantial value within it. Riding on his established market value, by producing numerous versions and editions of the Dollar Sign, Warhol essentially created and printed his own pseudo-currency. As in all currency, the value is dependent on its circulation. Since its debut, the series has proved immensely popular, perhaps comparable to the Campbell’s Soup Cans, and to this day, it is a staple in any auction house that regularly carries his work. Since Warhol’s death in 1987, the value of his work has risen steadily with no indications of decline, and his works are among the most expensive artworks ever sold. His 1963 screen prints Eight Elvises and Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) both sold for over a hundred million US dollars.

The success of Andy Warhol and the Pop Art movement as a whole reflected the rise of consumer culture in post-war United States. The pinnacle of Warhol’s career also coincided with the economic legacy of the Reagan era. Similarly, the rise of Chinese Contemporary Art was built on China’s economic reforms of the 1980s. Political Pop, the Chinese art movement directly influenced by Pop Art in the West, emerged in response to the drastic social change brought on by the reforms, highlighting the contradictions between China’s new capitalist tendencies and the nation’s past socialist ideals. In Wang Guangyi’s 1994 painting Great Criticism – Coca Cola, the artist boldly juxtaposes imagery of communist propaganda with a popular consumer brand from the West. Xue Song; however, takes a more subtle approach. In Xue’s renditions of the Coca-Cola bottle or Marilyn Monroe, the subject is often depicted as a silhouette, in which the outline is filled with hundreds of collage scraps. The juxtaposition exists between the image of the silhouette and the many images of the collage scraps, which prominently feature cultural or historical images of China. Similarly, this juxtaposition of cultures and values is seen in Wei Guangqing’s Jin Ping Mei or The Plum in the Golden Vase series, where 17th-Century Chinese erotic woodblock prints are overlaid onto a backdrop of American Pop artist Robert Indiana’s iconic letters Love. The clear social commentary and strong visual impact of Political Pop resonated well with Western audiences, and Contemporary Chinese artists of this generation in general witnessed increasing exposure in high-profile international shows, such as Mahjong – Contemporary Chinese Art from the Uli Sigg Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Bern in 2005, in which Wang Guangyi, Wei Guangqing, and Xue Song all participated.

The international recognition of Contemporary Chinese art soon led to a growing domestic demand in China. Paired with its growth as one of the fastest growing economies in the world, this triggered an exponential increase in the number of museums, galleries, and auction houses across the nation. In 2000, China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan contributed only one percent to the global art market, while in 2020 it has climbed to twenty percent, on par with the United Kingdom as second largest markets in the world after the United States.[2] In addition, while the two Western countries saw annual sales drop by over twenty percent due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the sales of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan fell by only twelve percent, achieving an estimated total of ten billion US dollars.[3] During this meteoric rise, Xue Song was careful not to lose sight of the path of his career. While many of his contemporaries burned out, either in terms creative output or market response, Xue Song continues to be a highly active member of China’s Contemporary art scene, regularly participating in high-profile art fairs including Art Basel, Hong Kong and Art Taipei, and also large-scale exhibitions like his 2019 retrospective Phoenix – Art from the Ashes at the Long Museum, Shanghai. Xue Song’s continuing success reflects his understanding of his role as an artist in today’s society, as well as the conscious choices he makes in the management of his career, many of which parallel those made by his inspiration; Andy Warhol.

The relationship and comparison between Xue Song and Andy Warhol is significant in a number of ways. On a level of superficiality, it reflects the Chinese fascination with the West brought on by the reforms of 1980s, during which the unprecedented access to Western art, while still relatively limited, led to widespread experimentation that often resulted in imitation. In Xue Song’s own words, upon gaining access to printed illustrations of Western art after his move to the metropolitan city of Shanghai in 1985, he was particularly intrigued by Andy Warhol; a foreigner who painted portraits of the Chinese communist leader, Mao Zedong.[4] Warhol’s depiction of Mao began in 1973, one year after president Richard Nixon’s famous visit. The portraits caused significant controversy comparable to the presidential visit itself. However, during the early days of the reform, Chinese artists, including Xue Song, had very limited insight into the context of Warhol’s depiction, but they were nonetheless inspired to create their own renditions, which became one of the most iconic and frequently depicted subject matter of Contemporary Chinese art throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s. Xue Song’s depiction of the Coca-Cola bottle; on the other hand, maintains a deeper connection to the source material. Similar to Andy Warhol’s original belief, the popular soft drink and its iconic image was seen by Xue as an idealized symbol of Modern culture. However, developing on Warhol’s idea, the drink and the culture it symbolized was even more sought after to the Chinese artist. It appealed to him as an exclusive foreign culture of not only consumer pleasure but also basic material comfort, and its growing accessibility signalized the coming of a new age in China and the rise of a middle class with tremendous consumer spending power, which paralleled the same economic phenomenon in post-war United States several decades earlier.

Beyond stylistic homages, Andy Warhol’s favorite theme of consumer culture is also prevalent throughout Xue Song’s art. As a byproduct and visual manifestation of consumerism, advertisement has become synonymous to the culture itself. Xue Song believes; rather than political, religious, or folk influences, commercial advertisement has the strongest impact on contemporary visual culture, and is essentially an unavoidable reality of everyday life.[5] Consequentially, this mode of visual communication is one he and his viewers are most familiar with. He has therefore made the conscious decision to adapt this mode of communication into his own visual style. Due in part to his training in stage design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy, Xue Song enjoys and excels in working with bright commercial colors and direct imagery. He regularly uses commercially-available colors straight from the container and rarely mixes shades on the canvas in order to create a mass-produced look. Further placing the theme on a conceptual level, his collage scraps we’re often actual printed advertisements themselves, either of real-estate or other luxury commodities.

However, unlike Andy Warhol who celebrated consumer culture in all its glamour, Xue Song departs from the American artist’s attitude and grounds his art in the complex and controversial context of modern Chinese history and society. While Xue Song’s 2012 portrait Marilyn Monroe appears as glamorous as Warhol’s portrayals, the scraps of traditional Chinese calligraphy that compose the actress’ silhouette confusingly bare zero correlation with the subject matter. This juxtaposition of Chinese and Western culture is best exemplified in Xue Song’s ongoing New Landscape series. In the 2020 painting New Heights, the composition is split diagonally, with a mass of land on one side and a body of water on the other. The land portion, depicted in the manner of traditional Chinese landscape painting, consists of collage scraps of famous examples from the said tradition and represents Chinese art as a whole. In contrast, the water portion features masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and thereby represents Western art. The theme of East versus West is further reinforced by the symbolism of land and water, where the former represents the art of one’s native land, while the latter represents that which has been imported from overseas. Regardless of origin, the two portions are presented as equal halves baring equal weight, in which neither half is dispensable. As a Chinese Contemporary artist, Xue Song actively acknowledges the influence of Western art on his own practice, and has a sober understanding of its market appeal. This mirrors consumer culture in China as a whole, where the Chinese consumers crave commodities that appear foreign and fashionable in form, but also function in their domestic setting. As an active consumer himself, this is a notion crystal-clear to the artist.

With both Andy Warhol and Xue Song, the artists’ keen and almost instinctive understanding of consumer culture is largely due to their lifestyles. Like Warhol, who was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and moved to New York as an adult, Xue Song was born in 1965 in Dangshan of rural Anhui province and dreamt of living in Shanghai as a child before ceasing the opportunity to move there as an art student in 1985. Since his move, Xue Song quickly emerged at the forefront of Shanghai’s art scene, and was the first artist, followed by geometric abstractionist Ding Yi and painter Zhang Enli, to take up studio at 50 Moganshan Road in 2001. Today, known as M50, the once industrial area has grown into an art district comparable to New York’s SoHo. In addition to artist studios, galleries, design firms, M50 is home to numerous cafes and bars and is a popular gathering place for fellow artists, celebrities, and patrons, much like Warhol’s studio, The Factory.

In his association with celebrities, Andy Warhol also expanded into other fashionable ventures including managing experimental rock band The Velvet Underground and founding popular culture magazine Interview in 1969, as well as endorsing numerous products, ranging from record players and beta tapes to men’s hair products and fast food. As long as the venture was fashionable and helped equate the artist’s image with popular consumer items, Warhol welcomed it. Xue Song, on the other hand, exercises far more discretion. Due in part to his nature as a man of very few words, Xue has never sought out a partnership with a brand, but nevertheless cooperates willingly and effectively when approached. In 2010, creative director Paul Andrew of the Italian luxury giant Salvatore Ferragamo reached out to Xue Song for a partnership in conjunction with the World Expo set in Shanghai that same year. As 2010 was the year of the tiger in the Chinese zodiac, Xue Song created a memorable painting of two tigers that served as the design in a series of limited edition bags, purses, and wallets. The following year; Xue Song was approached by German designer furniture brand Domicil for the launch of their artist inspired collection, in which Xue Song’s colorful series Calligraphic Imagery was chosen as the printed graphic in a series of sofas and chairs. In 2017, upon the Swedish air purifier company Blueair’s entry into the Chinese market, Xue Song was invited to design and embellish the covers of serval promotional air purifiers, which were unveiled during opening reception of the Art 021 Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair. In line with the health-conscious direction of the brand, Xue Song chose from his 2015 painting Tribute to Rothko I, images of two red-crowned cranes, as the bird symbolizes longevity in traditional Chinese culture. In 2019, German automobile manufacturer Porsche worked in partnership with Xue Song in the debut of the brand’s first fully-electric and environmentally-friendly vehicle, the Taycan, in the Chinese market. For the commission, Xue Song chose a single word to signify human being’s ideal relationship with nature; harmony, and the Chinese calligraphy of the word was outlined on a large-scale canvas and adorned with beautiful images of nature, all of which was then transferred and airbrushed in exact detail onto the roof of a promotional model.

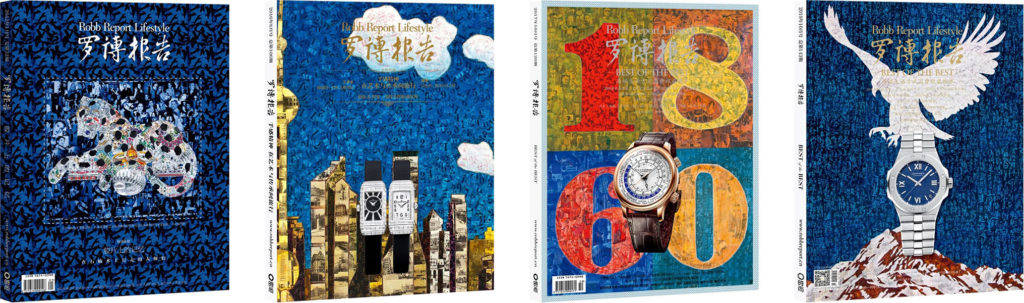

Again following Andy Warhol’s footsteps, Xue Song also blurred the boundaries between visual arts and entertainment in his partnership with Taiwanese singer and actor Jeff Chang. The album cover of the Pop singer’s 2018 album Song Era II features a close-up of Xue Song 2017 painting Peace Dove – Dialogue with Magritte. During the album’s press release and official announcement of the tour in Beijing, Chang’s music was played while a number of Xue’s paintings were prominently displayed, effectively blending two art forms into one experience for the audience. In summary, Xue Song’s relationship with luxury commodities is perhaps best illustrated by his position as the most frequently featured artist on the cover of the Chinese edition of American luxury-lifestyle magazine Robb Report. Since 2012, Xue Song’s artworks have graced the magazine’s covers four times, three of which were in partnerships with Swiss luxury watch brands Jaeger-LeCoultre and Chopard. Effectively promoting Xue Song’s personal image, the magazine features also include several studio photographs of the artist wearing the products while posing in front of his paintings, and thereby ties his personal image, his art, and the luxury products he endorses into one neat package for the consumer.

Andy Warhol famously once said, “say you were going to buy a painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you, the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.”[6] This quote not only reveals a prevalent psychology behind art collecting that many collectors choose to deny, but also demonstrates a sense of liberation Warhol enjoyed once he embraced it as fact. Xue Song too has brought this sense of liberation to his patrons. Expanding on his Symbol series, the nine canvases of his 2021 US Dollars pay tribute to Warhol’s Dollar Signs, but they also display his trademark technique of fiery collage. The works feature a wide range of imagery, from traditional Chinese landscape painting, calligraphy and folk art, to Renaissance, Baroque, and Impressionist painting, all of which are superimposed by the dominating symbol of the dollar sign, which in turn metaphorically adds a price tag to all the aforementioned works of art. This demonstrates Xue Song’s understanding of art as a consumer item, and its subsequent implications on his role as an artist. The understanding, along with the identification, establishment and reinvention of this role are all part of a complex and yet defining notion that artists have consciously dealt and struggled with since the early Renaissance to Contemporary art today. In Xue Song’s struggle, his grounded and compelling evaluation of his role as an artist is the ultimate value in his art.

1 Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B and Back Again (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975) 100-101.

2 Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2021 (Basel: MCH Swiss Exhibition and UBS, 2021) 17.

3 Ibid., 28-29.

4 Xue, Song. Interview. By Elaine Liu. 7 November 2017.

5 Ibid.

6Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B and Back Again (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975) 134.