by Elaine Suyu Liu (Translation by Timothy Chang)

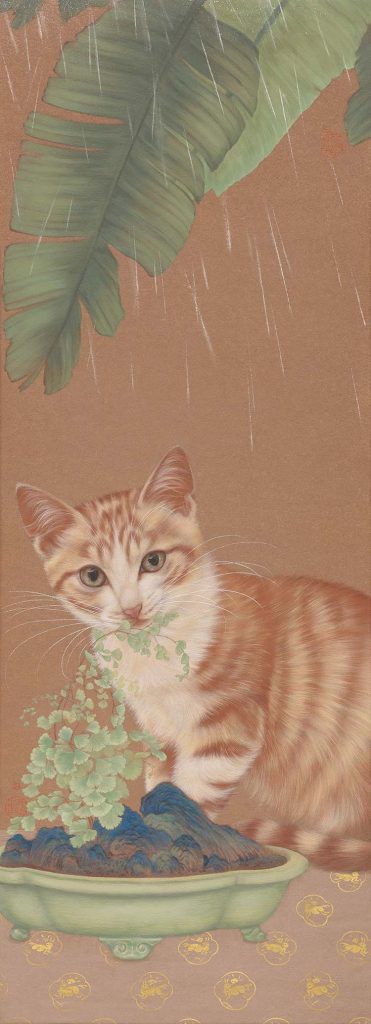

Rain on plantain leaves is a beloved Chinese cultural motif. Volumes of poetry celebrate the imagery, such as Ouyang Xiu’s (1007 – 1072) vivid and slightly melancholy verse “The long courtyard captures the twilight, Spells and spells of rain on plantain leaves.” It is also a favourite in literature, as seen in Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) painter Shen Zhou’s short prose “Listening to Plantain,” in which Shen writes “Plantains are still; rain is moving. Movement and stillness come together to become sound. This sound and the ears are compatible.”

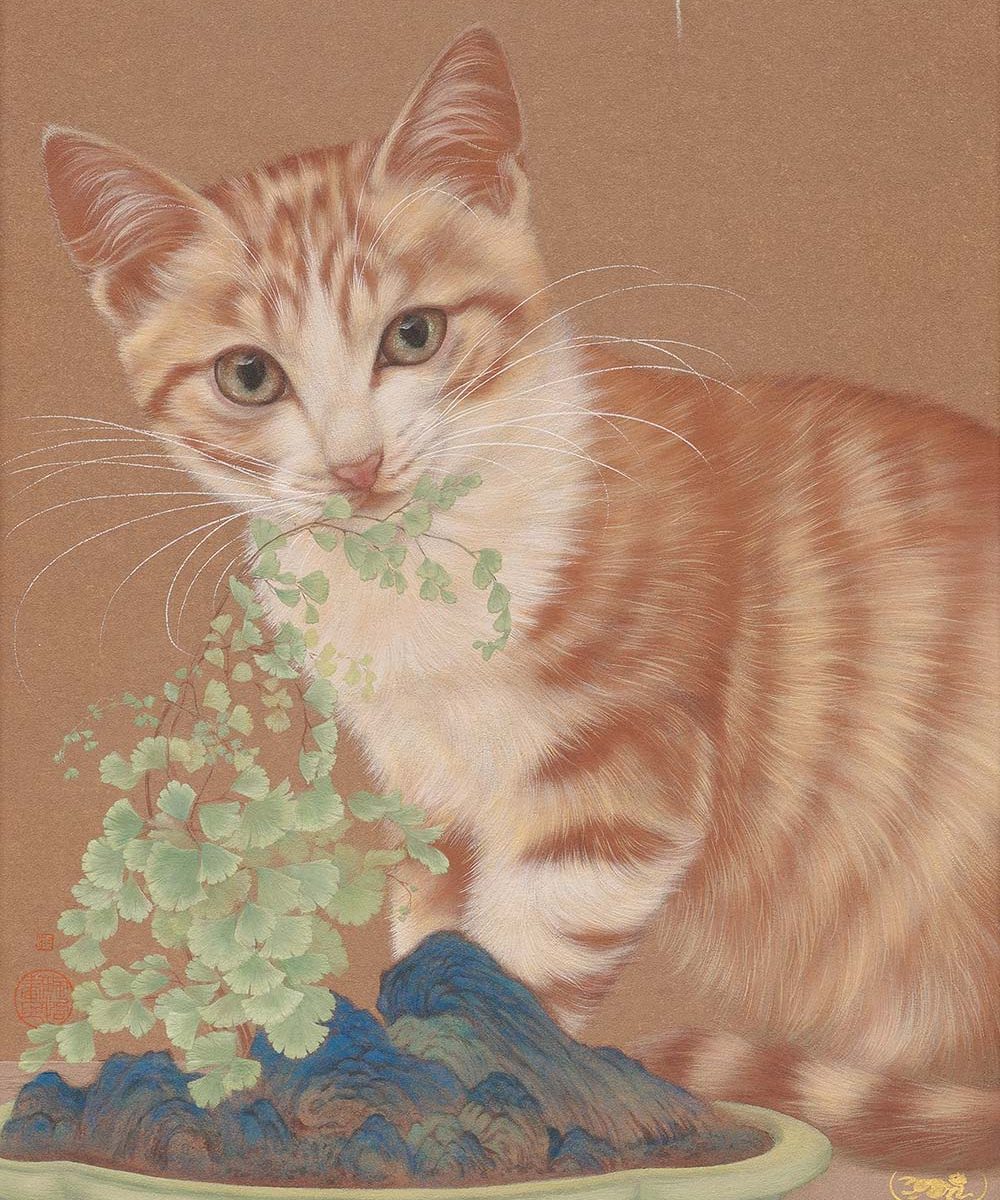

In Chen Pei-yi’s Fresh Greens, plantain leaves hang from the top of the painting towards to the lower left. The two central leaves differ in shape and colour, where a dark and tattered leaf shields a bright and wholesome one. The contrast symbolizes succession and growth, and also denotes the title of the painting. Strands of silk-like rain fall toward to lower left, in a crisscross with the plantain leafs, signalling a sense of motion. The light rain is fine, subtle, vaguely present, which is exactly where its beauty lies.

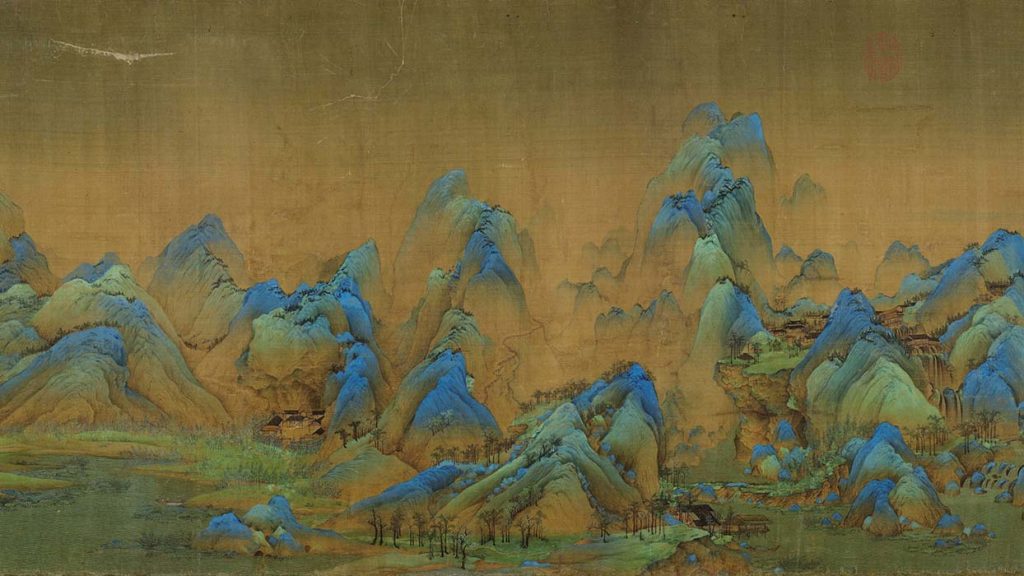

The sitter of the painting, a red tabby cat, is calm and unmoved by the rain or cares of the outside world. Instead, the feline is focused with eyes locked on the bonsai in the foreground. To the cat, the maidenhair fern’s long stems and fanning leaves serve as the perfect plaything. Its concentrated expression, graceful pose, and the fine hairs of its coat are all vividly rendered. Moving to the bonsai in the foreground, the delicate fern, the fine celadon planter, and miniature landscape contained within also reflect the artist’s brushwork. The planter is elegantly shaped with gently flaring sides divided into four lobes. Its four feet is adorned with an auspicious cloud pattern. The green of the celadon glaze not only echoes the maiden fern and plantain tree, but also the blue and green landscape of the bonsai itself, which captures the essence of Song Dynasty (960 – 1276) Wang Ximeng’s A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. Wang’s famed handscroll, housed in Beijing’s Palace Museum, is an exemplar of the Blue Green Landscape genre, in which mountainscapes are richly stylized with aquamarine blue and turquoise green. Chen’s homage to Wang’s Rivers and Mountains demonstrates her reverence to and mastery of the classical tradition, but more importantly her placement of the landscape inside a planter reveals her whimsical nature as an artist.

Relatred Journals

Essay

Nihonga in Taiwan

The term Nihonga was coined in Meiji Japan (1868 – 1912), during a time of growing nationalist sentiments brought on by the many challenges of Westernization. The genre came to represent a style of modern Japanese painting, as a response to the rise of Western art, which some nationalists saw as a threatening byproduct of Western imperialism.

Chen Pei-yi, Offering of Carp (detail), 2024 © Chen Pei-yi

Catalog Entry

Chen Pei-yi’s painting Playing with Lotus is a work built on strict classical training that encompasses both traditional and modern aesthetics. The vase and flowers on the left pays homage to Giuseppe Castiglione’s Gathering of Auspicious Signs of 1723, with variations such as the direction of rice stalks, the features on the vase, and the addition of the cat and textiles.

Chen Pei-yi, Playing with Lotus (detail), 2022 © Chen Pei-yi