Nihonga in Taiwan

by Timothy Chang

Born in 1984, Chen Pei-yi began her training in Eastern Gouache painting or Nihonga at Pingtung Normal University, and went on to complete a Masters in the discipline at Tunghai University in 2011.

The term Nihonga was coined in Meiji Japan (1868 – 1912), during a time of growing nationalist sentiments brought on by the many challenges of Westernization. The genre came to represent a style of modern Japanese painting, as a response to the rise of Western art, which some nationalists saw as a threatening byproduct of Western imperialism.

Ironically, Nihonga remains popular in Taiwan as a legacy of Japanese imperialism on the island. During the period of Japanese colonial rule between 1895 to 1945, the genre was officially taught in Taiwan and selected Taiwanese artists received further training in Japan.

However, when the governance of Taiwan was transferred the Republic of China in 1945, the new Chinese rulers saw Nihonga as strictly Japanese and its popularity as a threat to their political sovereignty over the island. Despite undergoing periods of government effort to marginalize the genre in favour of Classical Chinese painting, the practice prevailed. To this day, Taiwanese artists, scholars, and politicians debate the definition of Nihonga, from visual style, medium, cultural heritage, to tis name (Nihonga 日本画 literally means “Japanese Painting” in Japanese, which is why some prefer the more neutral term “Eastern Gouache”).

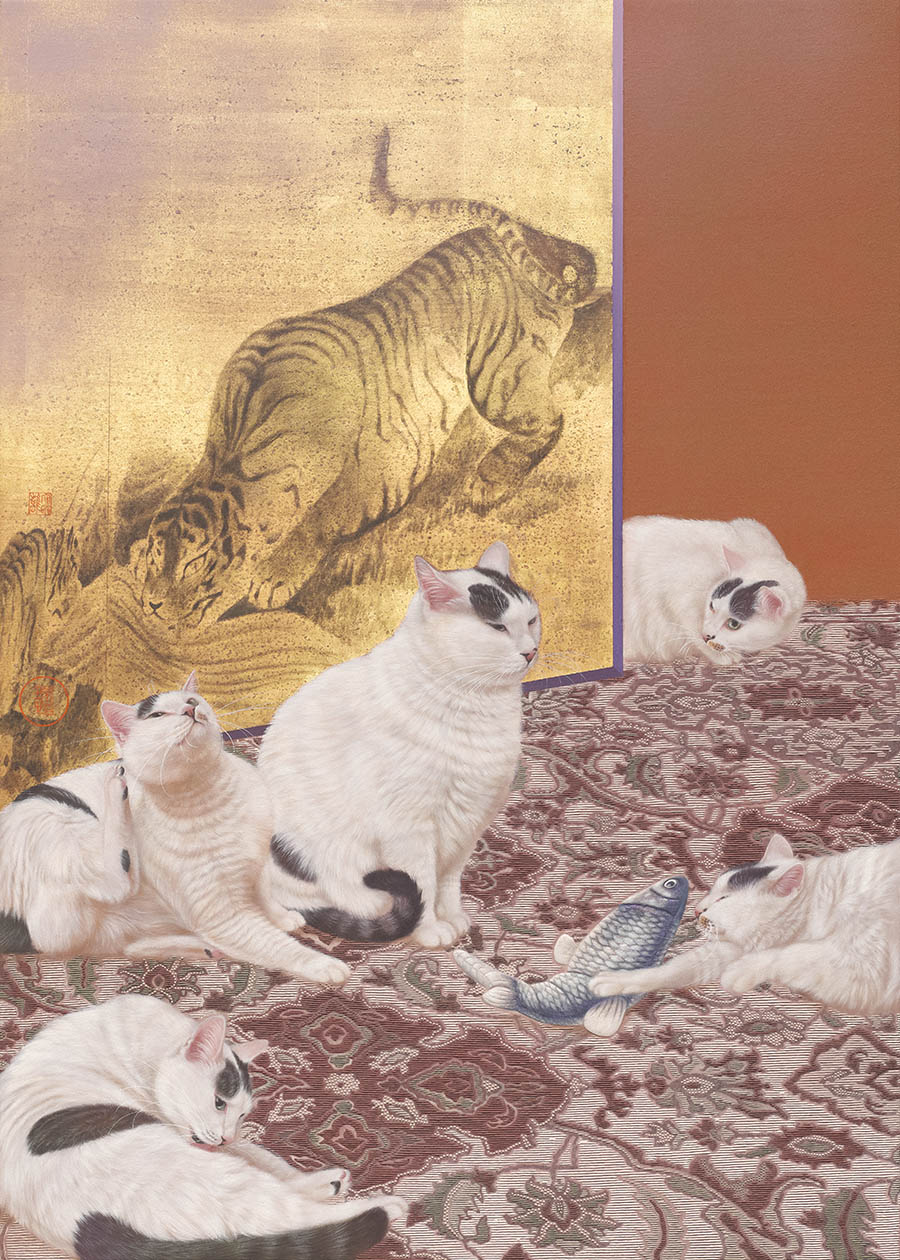

Chen Pei-yi dedication to Eastern Gouache or Nihonga is not only an insight to Taiwanese art history, but it also reflects the modern history of the island as a whole. While her paintings draws primarily from the Nihonga tradition, in terms of the use of natural mineral pigments and Japanese hemp paper, she also incorporates elements of Classical Chinese painting, such as traditional motifs and patterns and also dedicated seal inscriptions. Her visual style is also reminiscent of the Chinese Gongbi tradition, a realist technique of depicting still-life or figures. However, her style does not fall categorically into either the Gongbi tradition practised in China, nor Nihonga in Japan. It is a blend of two traditions that is uniquely its own.

Relatred Journals

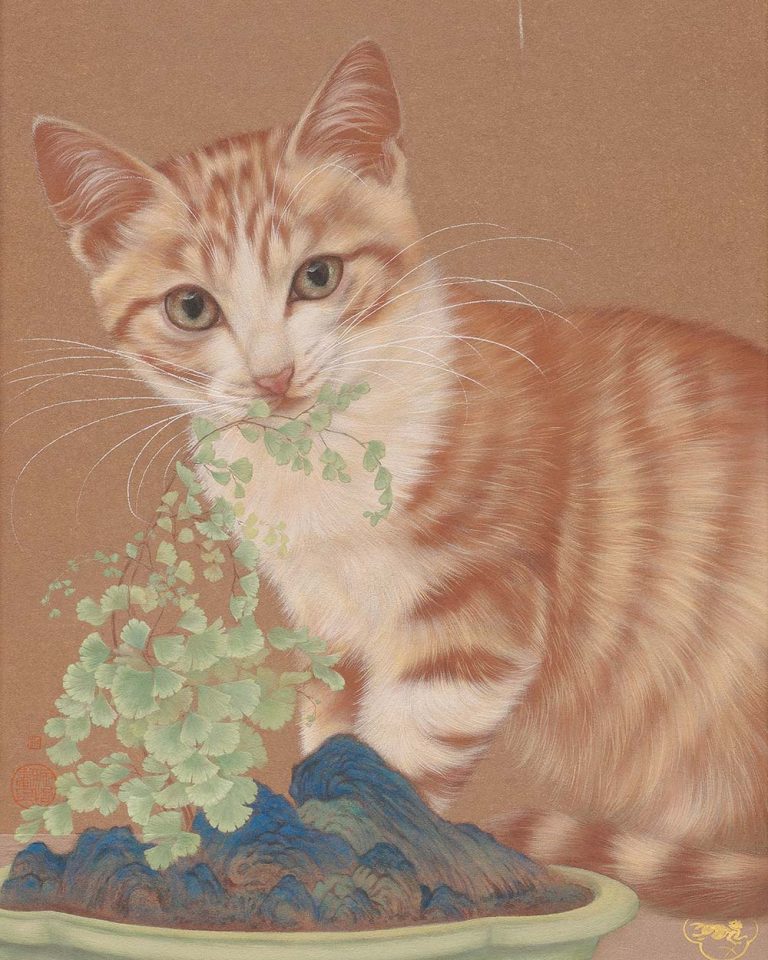

Fresh Greens

Catalog Entry

Rain on plantain leaves is a beloved Chinese cultural motif. Volumes of poetry celebrate the imagery, such as Ouyang Xiu’s vivid and slightly melancholy verse “The long courtyard captures the twilight, Spells and spells of rain on plantain leaves.” It is also a favourite in literature, as seen in Ming Dynasty painter Shen Zhou’s short prose “Listening to Plantain,” in which Shen writes “Plantains are still; rain is moving. Movement and stillness come together to become sound. This sound and the ears are compatible.”

Chen Pei-yi, Fresh Greens (detail), 2022 © Chen Pei-yi

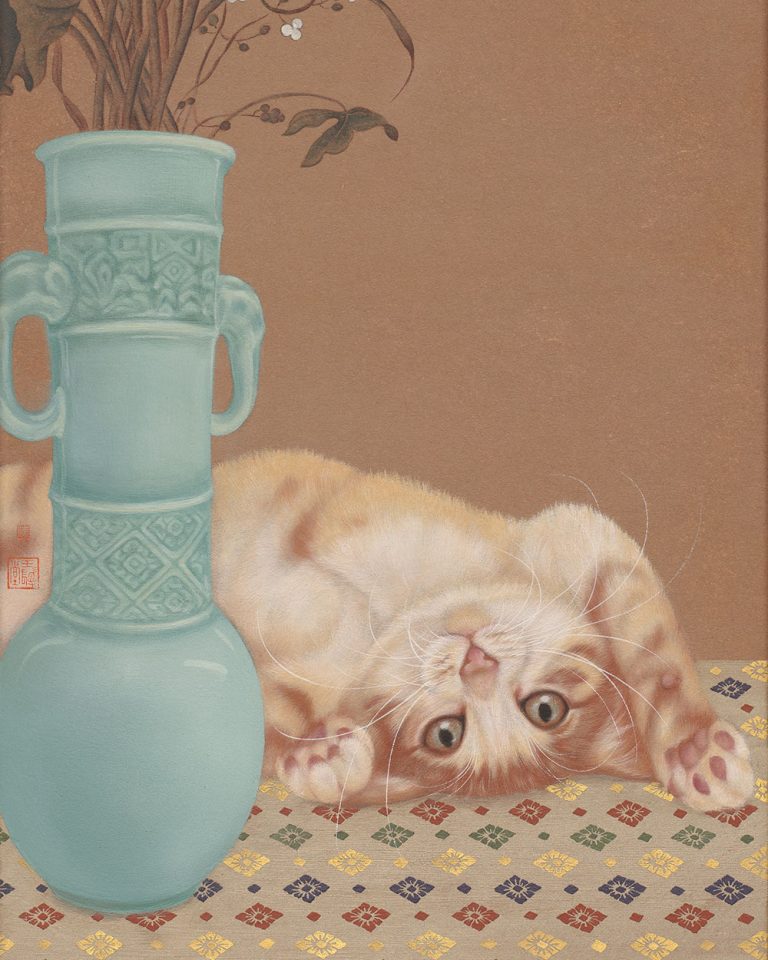

Playing with Lotus

Catalog Entry

Chen Pei-yi’s painting Playing with Lotus is a work built on strict classical training that encompasses both traditional and modern aesthetics. The vase and flowers on the left pays homage to Giuseppe Castiglione’s Gathering of Auspicious Signs of 1723, with variations such as the direction of rice stalks, the features on the vase, and the addition of the cat and textiles.

Chen Pei-yi, Playing with Lotus (detail), 2022 © Chen Pei-yi