The Flower of Plenary – Tzeng Yong-ning Solo Exhibition, Lofty Culture & Art, 2019.

by Elaine Suyu Liu (Translation by Timothy Chang)

Tzeng Yong-ning considers himself as a “barbarian,” because the environment he grew up in, was either the countryside, in mountains or by the sea. Due to his childhood interest in art and the encouragement of his father, who was an amateur photographer, Tzeng spent a great deal of time in nature, sketching, taking photographs, and ultimately leaving a large portfolio of botanical illustrations, all of which later served as inspiration for his art. His first solo exhibition came to be titled Barbarian Garden.

Barbarian Garden was a testament to Tzeng Yong-ning’s childhood experience with nature and art. Subsequently, the exhibition opened the doors to Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA), when Tzeng bid farewell to over five years of independent study in his hometown of Lukang.

Attending TNUA in 2005 was a turning point for Tzeng Yong-ning. The “barbarian” from central Taiwan faced a metropolitan city drastically different from the small town he knew so well. Fortunately, campus life was not too complicated. The real challenge was art, in learning and creation. In terms of selecting media, while oil, acrylic, watercolor, and Chinese ink were the staples at the University, Tzeng Yong-ning chose the “unprofessional” ball-point pen. Prior to his enrollment to TNUA, Tzeng had already worked with ball-point pen for several years, but if he continued with ball-point pen, why bother with university at all? Even if he wanted to pursue higher learning at university, he faced challenges different than students with conventional training, because there were no instructors who specialized in ball-point pen. The path he chose was one never chosen before. In terms of the media of ball-point pen itself, there are many technical limitations, whereas oil or acrylic paint can easily spread, blend, layer, and manipulate in general. Also, in comparison with watercolor or Chinese ink, the pen was not spontaneous and did not respond favorably to water. Each of these limitations Tzeng had to overcome and develop his own method of painting in response to convention media. Fortunately, TNUA was open to new ideas and encouraged students to explore freely. At the time, new media and experimentation was emerging in the art world, and Tzeng received the attention of faculty members and critics including Chu Teh-i, Ava Hsueh, and Lai Chi-man. During the installation of Barbarian Garden, Lai even picked out a piece and became Tzeng’s first collector.

In both 2004 and 2005, Tzeng Yong-ning was nominated for the Taipei Art Award, and in 2006, he won the Li Chong-sheng Foundation’s Visual Art Award, thereby becoming the youngest receipt in the Award’s history. He enjoyed even more recognition in 2008, when he received the Taiwan Award by the Asian Cultural Council, and its sponsorship for a travel and study program to China and Japan for several months. Since then, Tzeng has been invited to various group exhibitions, art fairs, and solo shows by commercial galleries, and has been well on his way in becoming a full-time artist. Also, much to the relief of his supportive parents, his was gaining popularity in the art market.

Since the validation of Barbarian Garden by the art world, Tzeng Yong-ning has produced new works every year, as well as developed several different series, and has essentially made his presence as an emerging young artist. In addition to sheer physical audacity, his art is a testament of his creative spirit. Working with ball-point pen is highly labour-intensive. There are no shortcuts, and no energy can be spared. Inside his studio, lies countless empty pen cartridges: an extraordinary sight. Furthermore, on the paper of his work, tens of millions of lines, build and overlap in complex images, filling the entire composition, in which each and every line represents the daily labour of the artist.

However, the real challenge to the labour is in form and content. In his mastery of the ball-point pen, Tzeng Yong-ning starts with fundamental elements. Starting with individual dots and lines, and progressing with intense repetition, dots and lines accumulate to shapes and planes, like cells reprocessing itself to create larger and more complex cells in an endless process. His works are not narratives, and are often simply titled Flower or Garden. With added complex geometric patterns, there is great tension between the figurative and abstract elements. He goes as far as to abandon the flower’s imagery and colors, to sketch compositions exclusively with lines. The trace or imprint of the ball-point on the paper reflects his strong artistic will.

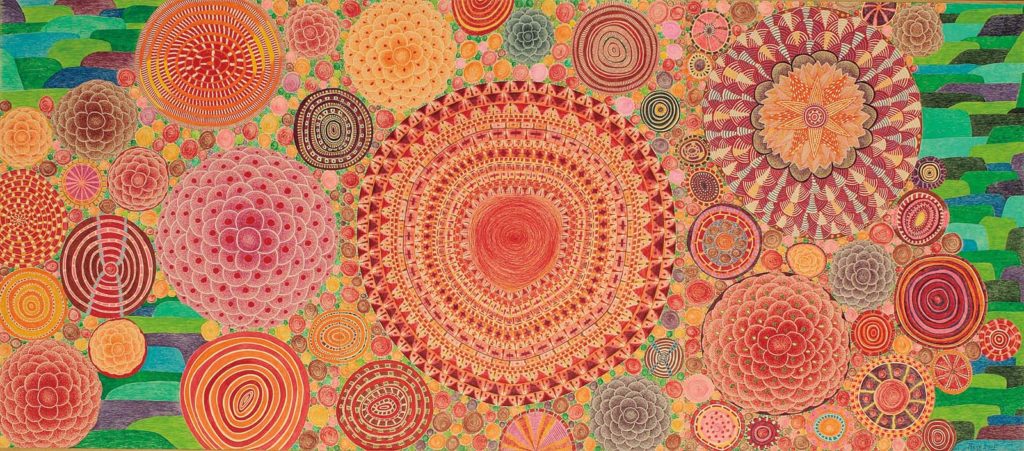

Tzeng Yong-ning’s relationship with the ball-point pen continues to grow and develop.This year in 2019 his newest series, Flowers of Plenary, featuring the addition of gold-foil reflects his spirit as an alchemist, in a never ending search for truth in art. The first work in the gold-foil series was debuted at the Glowing Nature exhibition this year at the Changhua Art Museum. Although it was not the largest piece in the exhibition, it received a great deal of attention. The circle is essentially a trademark in Tzeng Yong-ning’s work, but one with a diameter of over one and a half meters is brand new. Set in an encompassing sea of gold-foil, the work immediately grasps the viewer’s attention. Within the large circle are countless smaller circles of various colors, styles, and patterns. Each of the smaller circles interact and correspond with one another, in a sense of movement, in a image reminiscent of a mandala. In terms of the gold-foil that surrounds the large circle, the metallic shine is not only visually striking, but also sets an solemn and divine atmosphere. With the entire work framed by a deep purple wall, a further mysterious atmosphere is created, in a quasi-religious manner.

The term mandala is Sanskrit in origin meaning a divine circle, center or gathering, and is a geometric configuration of symbols that traces its origin to Hinduism and Buddhism with profound meaning. Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875 – 1961) believes that the mandala is a prototype of human collective subconsciousness, and that when one draws a mandala, one reflects the current state of mind as a form of art therapy.

This present exhibition is centered around three gold-foil works, also reminiscent of the image of mandalas. While Tzeng Yong-ning’s approach to art is fundamentally different than that of mandala painting, the visual imagery of a circle encompassed in gold is spiritually engaging. The shape of the circle is embedded in human history. A child picking up a pen instinctively draws circles, and individuals tend to gather in circles, the only shape that includes everyone equally. This preference for circles is found across different cultures. The ancient Greeks believed it was the most perfect shape, while the Chinese saw it as the most complete. Furthermore, from the prehistoric monument Stonehenge in England to the colosseum of ancient Rome, as well as the circular halos placed behind depictions of saints and deities in numerous religious traditions, the shape has also been associated with greatness and the divine. Circles are a key element in Tzeng Yong-ning’s art,. Found in nearly all of his works are circles of various sizes and patterns, symbolizing harmony, circulation, energy, and perfection.

Of course, other shapes are found in Tzeng Yong-ning’s art as well, but many are variations of the perfect shape, such as ovals or half circles. However, the circle is most prevalent and dominant. In the gold-foil Flower of Plenary series, a large circle dominates the composition, and is in turn filled with countless smaller circles, of various patterns, colors, and sizes. Packed together tightly, there is a sense of unity and harmony, due to the fact that all the individuals are grouped together, in a comprehensive whole. Yet, each circle is lively and energetic, seemingly expanding outwards, floating upwards, or squeezing each other. Encompassed in a field of gold, the large circle embodies a solemn planet, sitting scared and elegant in the serenity of space.

Tzeng Yong-ning has shared many times that while at work, when he hears the soft sound created by the friction of the ball-point pen on the corse surface of the paper, his mind becomes at ease. Sometimes it reminds him of the sound of his mother sowing, that is the swaying sound of the peddle of a traditional sewing machine. It is a rhythm he is accustomed to and a source of comfort, similar to the effect of creating a mandala.

Gold-foil in an integral part of the Flower series. It is his masterpiece of the year. Applying the foil itself is also labour-intensive, as well as unforgiving in terms of mistakes. He had worked with the idea in his head for a long time, and had bought the foil in a temple in Kyoto, Japan, over five years ago, but the idea only came to fruition this year. Why gold foil? It too is related to his childhood and his hometown of Lukang. Having spent many childhood years, playing in and out of the many historic temples throughout the town, the architectural elements and iconography of the temples became integral to his understanding and appreciation for art and culture. During his trip to Kyoto, visiting temples was the most memorable. In addition to how the architectural space is conceived and functioned, he was most impressed by the abundance use of gold. Symbolizing dignity and divinity, and color gold is commonly found throughout temples, and was an element Tzeng Yong-ning recognized since childhood. He also found the use of gold-foil in Kyoto more elegant and brilliantly applied than the temples in Taiwan, and there he decided to purchase some for future use, despite the costly nature of the material.

Tzeng Yong-ning prefers bright colors, such as the yellow often found in his works, which brighten up his compositions. Gold is essentially a brighter and shinier shade of yellow. The color gold directly alludes to the material gold, which represents power and wealth. Throughout history, gold is commonly used in works of art, such as in portraits of nobility, or the religious iconography of the Medieval Period. During the Renaissance, the Three Graces in Sandro Botticelli’s (1445 – 1510) Primavera are adorned with flowing golden locks, while Titian (1490 – 1576) was celebrated for his mastery of color, especially for his preference for the divine color. Closer to modern times, Austrian Symbolist Gustive Klimt adopted the gold as the primary color in his art, with the result being highly decorative and strongly mysterious. In addition to just the color, Klimt applied gold foil to his paintings, furthering the visual effect of the color. Klimt also employed the use of various geometric shapes and patterns, such as swirls and circles, to create a striking and pleasing image. The same use of shapes and patterns is found in Tzeng Yong-ning’s work, and with the further incorporation of gold-foil, similarities between Tzeng and Klimt become increasingly abundant, especially the sense of romanticism, aura of divine mystery, and artistic passion.

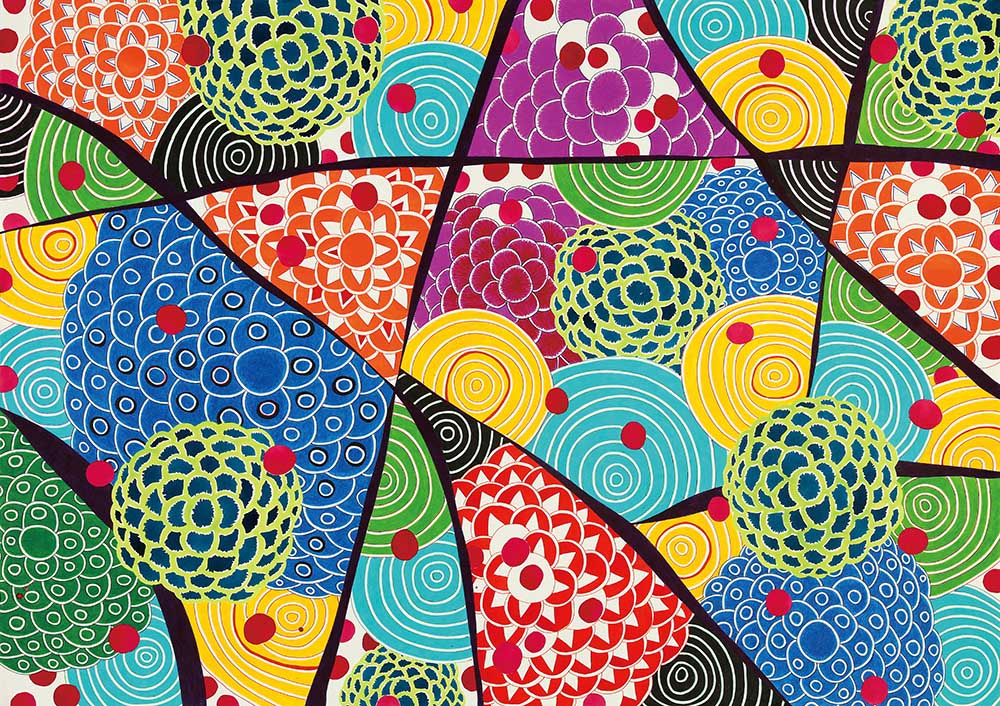

Tzeng Yong-ning’s works are filled with the sense of movement. Some are patterned rhythms, while others are wholly dynamic, filed with momentum and life. In Swaying Flower 01, Swaying Flower o2, Swaying Flower 03, Bloom 64, and Bloom 65 some triangles appear similar to the leaves of plants, and their repetition simulates organic growth. Their presence also provides variation and contrast to the predominances of circles.

In recent years, Tzeng Yong-ning has become increasing proficient in the use of geometric shapes. Such use engages the composition, heightens the sense of depth and three-dimensionality, and thereby challenges the limitations of the ball-point pen. Furthermore, the shapes are not represented with simple lines, but with planes of colors. In the exchange of colors, circles overlap and interact with various shapes, seemingly organically and full of rhythm. As there is a certain order or pattern to the arrangement or progression of shapes, the composition does not descend into chaos, which is often a challenge faced by the artist, to be overcome with vision and perseverance.

Despite the success of the Barbarian Garden and the secure foothold it created, Tzeng Yong-ning never dared to slow down in his art. From theme to content, from composition to size, as well as the complexity of each image and the constant renewal of his will to create art, he has the spirit of an alchemist. The goal of alchemy is not to create gold, but to create the purest substance, and to find the truth within, that is the ultimate pursuit in Tzeng Yong-ning’s art.

Relatred Journals

Essay

Primitive Landscape of Belief

The term “primitive” can be defined as an initial stage in evolutionary development. “Ecology” is the state in which organisms live and adapt in a given natural environment. Therefore, “primitive ecology” refers to an ecosystem independent of and undisturbed by external human activity. To borrow terms and definitions from the discipline of ecology to describe Tzeng Yong-ning’s art of course evolves a certain degree of appropriation.

Empty Ball-point Pen Cartridges, Tzeng Yong-ning’s Studio, Guandu, 2019. Photo: Yu Ming-lung

Catalog Entry

Tzeng Yong-ning’s Newest Series

The seemingly abstract works by Tzeng Yong-ning are often embedded with traditional motifs reflective of the cultural heritage of his hometown of Lukang.

Longshan Temple, Lukang. Photo: T. Chang

Catalog Entry

Tzeng Yong-ning’s Landscapes, Passing Leaps and Bounds

Landscape – Uphill feature an ensemble of bizarre shapes stacked on top of each other. The ensemble appears to bare visual weight, especially in contrast to the small and large circles surrounding it.

Tzeng Yong-ning, Landscape – Uphill 04, 2020 © Tzeng Yong-ning