Primitive Landscape of Belief – Tzeng Yong-ning Solo Exhibition Catalog, NYCU Arts Center, 2022.

by Richard MC Chang (Translation by Timothy Chang)

The term “primitive” can be defined as an initial stage in evolutionary development. “Ecology” is the state in which organisms live and adapt in a given natural environment. Therefore, “primitive ecology” refers to an ecosystem independent of and undisturbed by external human activity. To borrow terms and definitions from the discipline of ecology to describe Tzeng Yong-ning’s art of course evolves a certain degree of appropriation.

Tzeng Yong-ning has created and maintained for himself a distinct environment. In this environment, his art flourishes. At the same time, it does not stray from where he started. Tzeng Yong-ning set off to become a full-time artist working with ball-point pens as his primary medium, which is exactly what he has achieved. This environment is idiosyncratic in that the exclusive use of the unconventional medium is distinct and essential to Tzeng’s artistic practice. His adherence to the ball-point pen parallels an organism that develops a specific set of adaptations for its chosen ecological niche. Unlike others in the surrounding environments, Tzeng Yong-ning’s unwavering spirit can be described as a primitive ecology of art.

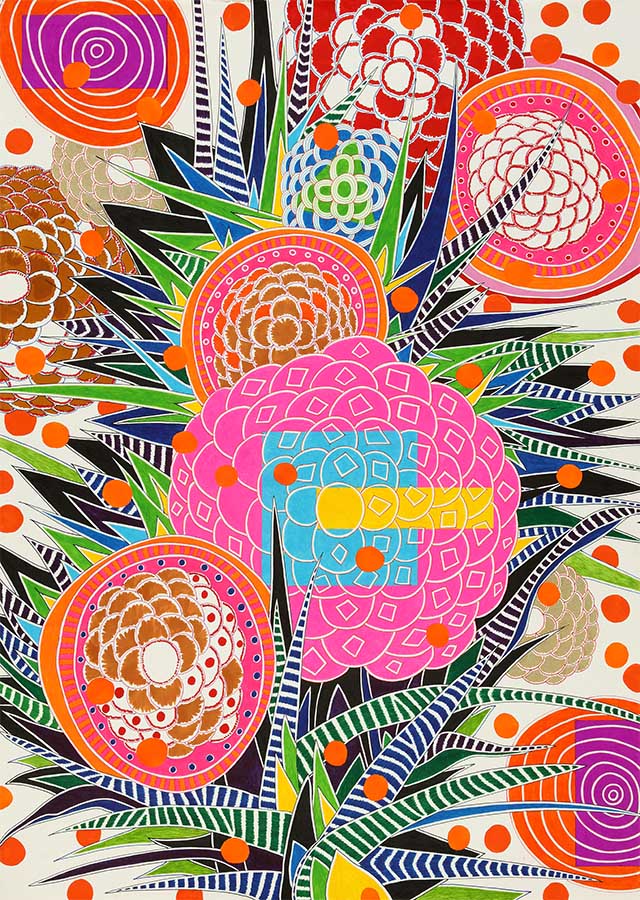

It can be said that Tzeng Yong-ning is a species endemic to Taiwan. He is the leading figure working with ball-point pen on paper in Taiwan, and draws inspiration from Taiwan. From historical temples and traditional woodwork in his hometown of Lukang to the countless mountain ranges throughout the island, Tzeng draws from these visual elements and transforms them into shapes and colors under his ball-point pen. Even the lollipop in his daughter’s hand is broken down into geometric shapes and elementary colors to be rearranged or expanded upon in his compositions.

As a subtropical island, Taiwan is rich in fauna and flora. Culturally, Taiwan celebrates a diverse history of southern Chinese settlers and indigenous peoples, whose different traditions have shaped the colorful architecture heritage of Taiwan. Given the accessibility of hardwood trees that flourish in the island’s subtropical climate, temples were adored with elaborate woodcarvings, such as lattice windows, reliefs, and statues. All of these visual elements are deeply imbedded in Tzeng Yong-ning’s childhood, which he draws upon as nutrients in his growth as an artist.

Tzeng Yong-ning has made ball-point pens his primary medium for over twenty years. This has made his name synonymous with the ball-point pen in the art world. Although in his recent works, Tzeng has included acrylic ink and colored pencils, he treats all mediums the same as ball-point pens and never mixes colors.

By using commercially available colors without mixing, Tzeng Yong-ning creates a distinct visual style. Tzeng’s colors are saturated and often opposing. In his use of ball-point pens, he also employs a variety of gel pens with neon and metallic colors. In his rendering of shapes and patterns, he forgoes the use of shading. A sense of depth is instead conveyed through the imprint of the ball-point pen’s tip left on the paper. By applying pressure, Tzeng leaves marks throughout the composition to create a textural effect. All of these features combined give his work a sense of other-worldliness.

Initially, Tzeng Yong-ning selected ball-point pens as a primary medium out of convenience. There was no need for a palette or easel, no waiting for paint to dry, and no washing of utensils. Tzeng could start and finish as he liked. All he needed as pen and paper. However, as Tzeng gained maturity with the medium, developed a strong personal style, and grew professionally in his career as an artist with access to a studio, the convenience factor became less important. Instead, the visual impact of the medium became the main driving force.

In comparison to conventional painting, either acrylic or oil, ball-point pens do not allow for mixing pigments, adding layers, or building heavy texture. However, ball-point pens do leave imprints on the paper. As the tiny ball at the tip of the pen rolls across the paper, it flattens out the paper’s fiber and leaves a distinct mark. While these marks are hardly noticeable at first glance, they become very apparent upon inspection, and can be moving to the viewer, who recognizes the time and effort the marks records. If it was possible to install an odometer-like device that tracks the distance a pen travels across paper, a circular patch of solid color three centimeters in diameter may contains lines that stretch out to be over five meters. This is what is recorded in the texture of Tzeng Yong-ning’s art.

Suppose that a patch of color three centimeters in diameter does contain five meters of lines drawn by ball-point pen. The area of a three-centimeter circle is approximately four-square centimeters. The most common dimensions of Tzeng Yong-ning’s works measure 75 by 107 centimeters and has an area of approximately 8000 square centimeters, which is 2000 times larger than the four-square centimeters patch. If we estimate that over half of Tzeng’s entire image is covered by ball-point pen in an area of 8000 square centimeters, we come to the astounding conclusion that his average artwork is composed to 5000 meters or five kilometers of lines drawn by ball-point pen.

If Tzeng Yong-ning produces an average of twenty artworks every year, that is a hundred kilometers of ball-point pen lines every year. In the past twenty years that Tzeng Yong-ning has worked with ball-point pens, he has far exceeded the thousand-kilometer journey to travel around the island of Taiwan. Although, this is truly a labor-intensive undertaking, Tzeng Yong-ning believes the rustling sound of pens traveling across paper brings him peace and quiet. Unlike other paints or inks that can cover a large area relatively fast, pens can only work with one tiny line at a time. Perhaps it is due to this aspect of constraint that Tzeng finds peace.

Another feature of Tzeng Yong-ning’s art is the predominance of geometric shapes, either composed of smooth lines by ball-point pen or dabs of acrylic ink. Groups of circles or layers of squares, the ever-changing geometric shapes appear like flowers or microscopic cell. Through the strong visual contrast between forms and colors, the shapes appear three-dimensional despite the two-dimensional nature of the paper. The continuation of triangular shapes is visually similar to the cross-section of rocks, where each layer or sentiment defines a spatial boundary. While squares and rectangles often appear in Tzeng’s images, the shape does not often appear in nature, and therefore gives his work and artificial or surreal dimension.

In recent works, non-geometric shapes are also present. For example, in Bloom 64 and Bloom 65, curving lines like the crown of a pineapple or the tail of pheasant dominate the composition. In the Landscape – Uphill Series, organic lines are furthered developed into figurative expression, where the shape of trees become strongly evident. The non-geometric shapes break up the monotony of the composition, and at the same time strengthens the artwork’s connection with nature.

Prevalent throughout Tzeng Yong-ning’s different series is the ability to bring a sense of joy or wonderment to the viewer. When Tzeng’s artwork enters a given space, the endless shapes and abundance of colors come alive and leap off the image. The changing geometric patterns create a sense of movement, while the brilliant colors brighten up the room. Likewise, being in the same room, the viewer also experiences these uplifting effects. This phenomenon is what makes Tzeng’s artworks so fascinating.

Upon much thought, the ability of Tzeng Yong-ning’s artwork to move viewers and brighten up rooms perhaps comes from his use of commercially-available colors. In each of our childhoods, we more or less all had the opportunity to draw, most likely with crayons in kindergarten or color pencils in elementary school, most of which was done on paper. Therefore, all of us have the experience of using commercially-available colors on paper since an early age, which is not unlike Tzeng Yong-ning’s introduction to art. However, unlike Tzeng, very few of us were able to cultivate those early experiences into a life-time passion or career. Perhaps it is due to this childhood connections that allows us to access and resonate with his art.

Tzeng Yong-ning’s art is very rational. With amazing patience and perseverance, he continues to explore the endless relations between shapes, colors, and patterns. He then painstakingly creates composition after composition with infinite possibilities. While the possibilities are endless, so is his determination. Having set foot on this long and lasting path of art, he has set the boundaries to the environment in which he thrives. In this environment, we witness Tzeng Yong-ning’s primitive ecology of art.

Relatred Journals

Catalog Entry

Tzeng Yong-ning’s Newest Series

The seemingly abstract works by Tzeng Yong-ning are often embedded with traditional motifs reflective of the cultural heritage of his hometown of Lukang.

Longshan Temple, Lukang. Photo: T. Chang

Catalog Entry

Tzeng Yong-ning’s Landscapes, Passing Leaps and Bounds

Landscape – Uphill feature an ensemble of bizarre shapes stacked on top of each other. The ensemble appears to bare visual weight, especially in contrast to the small and large circles surrounding it.

Tzeng Yong-ning, Landscape – Uphill 04, 2020 © Tzeng Yong-ning

Essay

The Flower of Plenary

Tzeng Yong-ning considers himself as a “barbarian,” because the environment he grew up in, was either the countryside, in mountains or by the sea. Due to his childhood interest in art and the encouragement of his father, who was an amateur photographer, Tzeng spent a great deal of time in nature, sketching, taking photographs, and ultimately leaving a large portfolio of botanical illustrations, all of which later served as inspiration for his art. His first solo exhibition came to be titled Barbarian Garden.

Tzeng Yong-ning’s Studio, Guandu, 2019. Photo: Yu Ming-lung